This thing, whatever it is called, corona virus, novel corona virus, new corona virus, COVID 19, or COVFEFE 20

Mar 18, 2020 by S. C. Gwynne

Back in the good old days of the Cold War, when doomsday existed in the form of Russian or Chinese intercontinental ballistic missiles, we were all supposed to be terrified of nuclear annihilation. We were constantly reminded that the US alone had an arsenal big enough to destroy the world several times over, that we were all in great and collective mortal danger, and that we should be very, very afraid. I got the annihilation part when I was younger, but not the fear. If we were all going to die in global thermonuclear war, then what was the point of worrying? My death would coincide with a clean finish to the human species. Who would want to be alive anyway?

The thing to actually fear, I always thought, was a rocket with the name “Sam Gwynne” painted on it, and aimed at me. That idea is terrifying—as that Iranian general recently discovered. But I knew there was no such rocket, and I never lost sleep over the prospect of nuclear war.

Fast forward to 2020. I am no longer a carefree teenager or young adult with the luxury of laughing at death. Not only that, but at the age of 66, with a history of smoking, a recent respiratory illness, and a compromised immune system, I have become the thing I feared: a target. This thing, whatever it is called, corona virus, novel corona virus, new corona virus, COVID 19, or COVFEFE 20, is actually pointed at me. Not only me, of course, but other geezers like me. I have heard that millenials are calling it the “Boomer Remover” and they are right. This rocket does have my name on it.

So what does the intrepid writer do when faced with asphyxiation in a cold room somewhere, unattended, without doctors or ventilators? Worry about the gin supply, for one thing. I am willing to forego toilet paper and hand sanitizer, but not gin. If the latest estimates are correct—150 million Americans will be infected and 3 million will die—then we have to assume that the virus is crawling invisibly over everything that humans touch. Which means liquor stores. I would rather not have my epitaph read: “He traded his life for a liter bottle of Gordon’s and a four-pack of elderflower tonic water." So I have to find a gin delivery service. I am working on that. Otherwise I hunker down, which in the dictionary definition means “to squat or crouch” and which at my age is quite imposslble for more than about 10 seconds. In the current vernacular, it actually means “doing nothing useful for long periods of time.”

I do a few things. I walk the dogs with my wife. I chat with neighbors, keeping a distance of 10 feet. We seem to be in a competition with each other to see who can be the most pessimistic. I know many people who were blue-sky optimists just days ago. No longer. Now they use sanitary wipes on their delivered newspapers. These days optimists die hard.

But, seriously, what is a writer supposed to do? In times of crisis people need builders and doctors and scientists and engineers and social workers and lawyers, etc. They really don’t need writers. Writers are more or less useless for anything but entertainment. Reporters are something different; they perform practical services like telling us that there won't nearly enough hospital beds for the sick. They quantify the apocalypse, thereby boosting sales of Gordon’s gin.

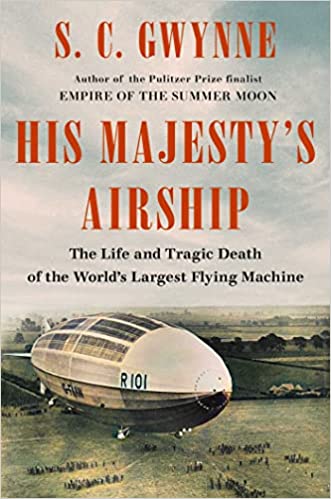

But I no longer work for newspapers or magazines, as I did for most of my career. I am a homebound historian in a world where all libraries are closed. It’s a curious feeling of utter uselessness. I submitted a book proposal last week about the early days of commercial aviation, which right now seems about as relevant as a book about pink bunny rabbits on the outer moons of Jupiter.

With nothing else to do, and no way to help anyone since I can’t really leave my house, I have decided to write a memoir. Or as my clueless neighbor pronounces it, a “mem-wah.” Don’t laugh. Actually, I laugh every time I see another review of a book by someone who grew up poor and abused, somehow went to Yale, then struggled with her own problems of drug abuse and self-loathing, not to mention her fraught relationship with her father. Is there no end to the market’s appetite for this sort of crap?

Anyway, my memoir will be nothing of the sort. My lovely and brilliant daughter, who was born when I was 40, knows very little about my life before her birth and virtually nothing about her wider family. Nor is she even curious to know it. So I will supply a need that doesn’t exist. I will write a letter to my daughter, for her eyes only. It will be a history of me and my family. I will put photographs and documents into it. This seems like a pretty good idea to me, especially right now. I mean, what if that rocket hits me?

That is what I will be doing for the next few months. (Even if I manage to sell this book proposal, I won’t be able to start working on the book in the near future. I need libraries. I need to travel.)

Still, I try to keep my spirits up. I went to the pharmacy a few days ago—before the woman in line in front of me delivered a rapid-fire sequence of sneezes that made me decide not to go there anymore—and picked up my usual prescription. The pharmacist asked me if I needed anything else and I answered “Oh, four or five bottles of hand sanitizer.” Everyone laughed. The sneezing woman even laughed. “Corona joke,” I said, and everyone laughed again.

The thing to actually fear, I always thought, was a rocket with the name “Sam Gwynne” painted on it, and aimed at me. That idea is terrifying—as that Iranian general recently discovered. But I knew there was no such rocket, and I never lost sleep over the prospect of nuclear war.

Fast forward to 2020. I am no longer a carefree teenager or young adult with the luxury of laughing at death. Not only that, but at the age of 66, with a history of smoking, a recent respiratory illness, and a compromised immune system, I have become the thing I feared: a target. This thing, whatever it is called, corona virus, novel corona virus, new corona virus, COVID 19, or COVFEFE 20, is actually pointed at me. Not only me, of course, but other geezers like me. I have heard that millenials are calling it the “Boomer Remover” and they are right. This rocket does have my name on it.

So what does the intrepid writer do when faced with asphyxiation in a cold room somewhere, unattended, without doctors or ventilators? Worry about the gin supply, for one thing. I am willing to forego toilet paper and hand sanitizer, but not gin. If the latest estimates are correct—150 million Americans will be infected and 3 million will die—then we have to assume that the virus is crawling invisibly over everything that humans touch. Which means liquor stores. I would rather not have my epitaph read: “He traded his life for a liter bottle of Gordon’s and a four-pack of elderflower tonic water." So I have to find a gin delivery service. I am working on that. Otherwise I hunker down, which in the dictionary definition means “to squat or crouch” and which at my age is quite imposslble for more than about 10 seconds. In the current vernacular, it actually means “doing nothing useful for long periods of time.”

I do a few things. I walk the dogs with my wife. I chat with neighbors, keeping a distance of 10 feet. We seem to be in a competition with each other to see who can be the most pessimistic. I know many people who were blue-sky optimists just days ago. No longer. Now they use sanitary wipes on their delivered newspapers. These days optimists die hard.

But, seriously, what is a writer supposed to do? In times of crisis people need builders and doctors and scientists and engineers and social workers and lawyers, etc. They really don’t need writers. Writers are more or less useless for anything but entertainment. Reporters are something different; they perform practical services like telling us that there won't nearly enough hospital beds for the sick. They quantify the apocalypse, thereby boosting sales of Gordon’s gin.

But I no longer work for newspapers or magazines, as I did for most of my career. I am a homebound historian in a world where all libraries are closed. It’s a curious feeling of utter uselessness. I submitted a book proposal last week about the early days of commercial aviation, which right now seems about as relevant as a book about pink bunny rabbits on the outer moons of Jupiter.

With nothing else to do, and no way to help anyone since I can’t really leave my house, I have decided to write a memoir. Or as my clueless neighbor pronounces it, a “mem-wah.” Don’t laugh. Actually, I laugh every time I see another review of a book by someone who grew up poor and abused, somehow went to Yale, then struggled with her own problems of drug abuse and self-loathing, not to mention her fraught relationship with her father. Is there no end to the market’s appetite for this sort of crap?

Anyway, my memoir will be nothing of the sort. My lovely and brilliant daughter, who was born when I was 40, knows very little about my life before her birth and virtually nothing about her wider family. Nor is she even curious to know it. So I will supply a need that doesn’t exist. I will write a letter to my daughter, for her eyes only. It will be a history of me and my family. I will put photographs and documents into it. This seems like a pretty good idea to me, especially right now. I mean, what if that rocket hits me?

That is what I will be doing for the next few months. (Even if I manage to sell this book proposal, I won’t be able to start working on the book in the near future. I need libraries. I need to travel.)

Still, I try to keep my spirits up. I went to the pharmacy a few days ago—before the woman in line in front of me delivered a rapid-fire sequence of sneezes that made me decide not to go there anymore—and picked up my usual prescription. The pharmacist asked me if I needed anything else and I answered “Oh, four or five bottles of hand sanitizer.” Everyone laughed. The sneezing woman even laughed. “Corona joke,” I said, and everyone laughed again.